Battery boom: Central Mass. invests billions in the electric vehicle market

Photo | Courtesy of Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Yan Wang first joined Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 2011 and is now director of its Electrochemical Energy Laboratory.

Photo | Courtesy of Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Yan Wang first joined Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 2011 and is now director of its Electrochemical Energy Laboratory.

Yan Wang had a feeling. Ten years ago, the Worcester Polytechnic Institute professor of mechanical and materials engineering knew it was only a matter of time before lithium-ion batteries would become an even bigger part of our everyday life. The batteries were already in laptops, smartphones, and baby monitors, but an even bigger market awaited: cars.

Wang foresaw how they’d fit into the future of electric vehicles, and his hunch was when the technology caught up and the costs dropped, there would be a market for battery research.

“Eleven or 12 years ago, not many people were interested in battery recycling, to be honest,” Wang said. “But I convinced myself of two things: One is I believe that there will be a big win for EVs. I was convinced eventually the industry, the auto industry, will adopt EVs.

“And the second thing I said was it is a matter of time that we need to recycle those batteries because the lithium batteries in the EVs can [work] eight years, 10 years, but eventually they have to be recycled. If I trust the EV industry, maybe it's not today; maybe it's tomorrow,” he said.

With that feeling, Wang started digging into recycling. Lithium batteries are made up of materials not ubiquitous around the globe. Countries, governments, and economies would need to mine and move them, and they’d be held at the whim of trade and supply chains. Cobalt, graphite, and nickel are just a few of the rare metals used needing to be recycled.

“The U.S. produces 10% of lithium batteries in the globe, but we don't produce any of those materials,” Wang said. “We produce less than 1%. That means we have to rely on other countries and have to import those critical resources so if we can develop an internal, domestic material supply chain, I think it will be good for the EV industry in the U.S.”

Spinning out a company

Wang’s research led to the 2015 creation of the company Ascend Elements in Westborough, which recycles battery materials. Ascend has grown into a global player, is building a $1-billion, 500,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in Kentucky, received $480 million in grants from the U.S. Department of Energy to build out its operations, is constructing another $43-million facility in Georgia, and in October partnered with the South Korean battery material company EcoPro Group to use Ascend’s recycled materials.

Wang’s research that started Ascend was about trying to preserve cathode material like cobalt, nickel, and manganese, which are extremely expensive raw materials to mine and source. At the time, Wang said, lithium was cheap, and some of it could be recovered after the other metals were extracted from the battery to be recycled and used again. Now, though, the price of lithium has skyrocketed. The price of lithium has risen from $6,128 per metric ton in August 2020 to $59,928 per metric ton in August 2022, according to a report by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

Wang, though, was already on his way to exploring how to extract nearly 100% battery-grade lithium from recycled batteries, and this year he published a paper on it in an issue of the science journal Green Chemistry.

Why all of this research? Because as the EV market continues to grow, there will be a greater need to create an independent supply chain of the materials used for batteries. While renewable energy can be created without burning fossil fuels, it does take rare materials and elements to store that energy for use. With that comes a cost, and as Wang sees it, the cost will grow unless we figure out how to harness the materials we’ve already harvested.

“When you consider the production ramping up initially, you need lots of batteries, lots of battery materials, but you don't have that many battery materials to be recycled,” Wang said. “Initially, you need loads of new materials, but eventually if the spent battery is the same with the new batteries, in principle you don't need new materials. But also those are critical elements – it's a critical resource– eventually those will be used up if you don't recycle.”

An inflection curve of adoption

Lithium-ion batteries aren’t going away. The once humble battery is becoming more and more important as we try to move away from fossil fuels to power our lives, and specifically to power how we move across the earth. With that, a new economy has emerged based on technology around since the 19th century.

The battery was invented in 1800 by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta, and through the marvels of science, it has evolved from a simple power source into a remarkable part of our everyday lives. They’ve become ubiquitous. Every holiday or birthday (especially if you have small children) there’s the moment of panic: Did I forget the batteries? Does it come with batteries? Now, though, batteries are the future and a new source of exploration and invention and have become an even bigger part of the economy, thanks to electric vehicles growing in popularity.

The electric vehicle boom began in 2018 with the introduction of the Tesla Model 3, which was somewhat affordable compared to other electric vehicles. Since then, electric vehicle sales have continued on an upward trajectory.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, its rebate program, MOR-EV, has issued 26,240 rebates to people who have bought electric vehicles since the program went into effect in 2014: battery EVs account for 15,982 vehicles, and hybrid vehicles for 10,228. The DOER tracks the purchase of EVs only by customers who submit an application for a rebate, so not all electric cars purchased are not included in this tally.

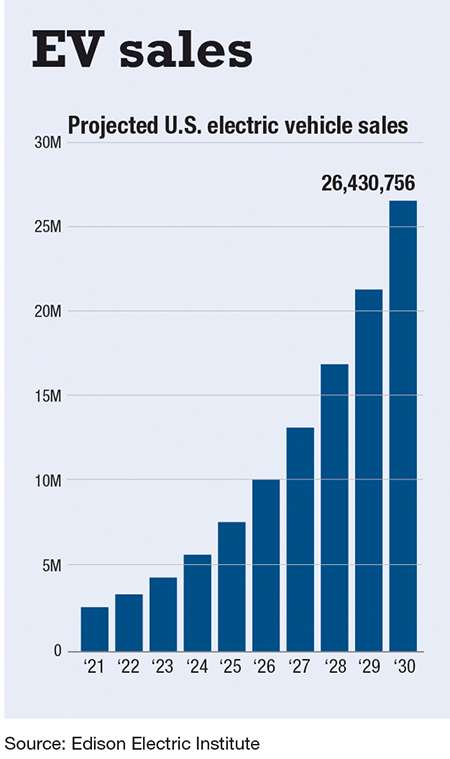

Electric vehicle sales are outpacing projections, said Charles Satterfield, senior manager of electric transportation with the national electric utility trade organization Edison Electric Institute.

“Obviously things were curtailed a little bit during the COVID years, so it was not a straight line in the upward adoption curve, but that has resumed now recently,” Satterfield said. “We're seeing month over month, quarter over quarter, year over year large increases in sales figures.”

In 2021, electric vehicles accounted for 2-4% of all light-duty vehicle sales, but this year that number has grown to 8%, Satterfield said.

“We are really starting to see the inflection curve of the adoption,” he said.

Servicing EV infrastructure

With that adoption rate comes a need for infrastructure. If cars are no longer using gasoline, then there needs to be a fuel source nearby to abate the fear of being stranded without a place to charge your car. As part of the 2022 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the federal government plans to invest $5 billion to add charging stations along major corridors and less than one mile off highways, similar to the current gasoline station infrastructure.

The U.S. will need 13 million charging ports, the vast majority of which will be in people’s homes, Satterfield said. However, 140,000 of those need to be public fast-charging ports, and right now, 14,000 have been built, if Tesla charging stations that only work with Tesla vehicles are counted.

“We're gonna need to dramatically increase those figures between now and 2030 to support the number of vehicles we believe are going to be on the road,” he said.

With that increase of chargers and cars, the batteries need to be safer and even more efficient.

Northborough technology firm Aspen Aerogels makes aerogels for a multitude of technical applications like thermal insulation. Aspen started by creating aerogels for sea pipes before discovering the materials are perfectly suited for lithium batteries.

“We found our way into electrification because there was this collusion of opportunities where electrification has taken off both from a political perspective and also because it's the right thing to do,” said Keith Schilling, Aspen’s senior vice president of technology.

The aerogel the company developed protects batteries from thermal runaway, which is when the cell of a battery begins a positive feedback loop and overheats, which can jump to other cells in the battery and cause them to burn at more than 1,000 degrees Celsius. Because cells swell when charging, a barrier between them not only needs to protect against heat and fire, which aerogels do well, but need to grow and shrink with the cells.

“You think of it as kind of the airbags of a vehicle,” Schilling said.

Aspen has partnered with General Motors in the Detroit car manufacturer’s pursuit of a line of electric vehicles safe from thermal runaway, which is rare but is exceedingly dangerous. With the success it found in this application, Aspen has begun to devise more ways to get involved in lithium battery production, which led it to look for a new place to house an entire division of its company dedicated to one sector of the economy.

That new home will be the 59,000 square feet of space in Marlborough it is leasing as a research-and-development center to expand its foothold in the EV market, on top of a $575-million facility the company is building in Georgia.

While the technology in the batteries has become safer and more reliable, the next great improvement has been the ability of manufacturers to create battery systems that can drive further. Drive distances increase each year. The 2017 Chevy Bolt had a top-mile distance of 238 miles, while the 2022 version can hit a top mile distance of 259 miles. On top of this, states like California are banning sales of new combustion engine vehicles in 2030. Its new car market will be solely EVs. Massachusetts isn’t far behind in its plans to prioritize removing fossil fuel burning vehicles from the new vehicle market to reach its own climate goals.

“We are expecting more than 26 million EVs on the road in 2030,” Satterfield said. “That is roughly close 10 times increase of how many were on the road at the beginning of 2022.”

With those numbers comes possibilities and more opportunity for companies to get into the marketplace, to push enhancements and the technology further. The research Wang, Ascend Elements, Aspen Aerogels, and others are doing will become more important. The battery boom is only beginning, and the construction on the runways has started.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to Yan Wang's last name as Yang twice.

0 Comments